FLEET researchers have designed a rapid nano-filter that can clean dirty water over 100 times faster than current technology.

Simple to make and simple to scale up, the technology harnesses naturally occurring nano-structures of aluminium hydroxide that grow on liquid metal gallium.

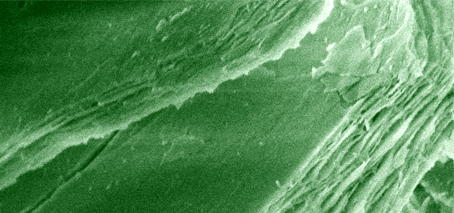

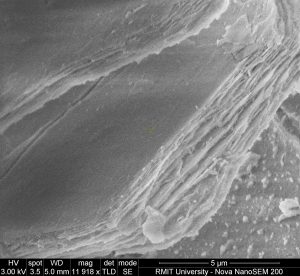

Electron microscopy image of products obtained from liquid metal based synthesis, showing 2D sheets of aluminium hydroxides

The researchers behind the innovation at RMIT University and UNSW have shown it can filter both heavy metals and oils from water at extraordinary speed.

RMIT researcher Dr Ali Zavabeti said water contamination remains a significant challenge globally – 1 in 9 people have no clean water close to home:

“Heavy metal contamination causes serious health problems and children are particularly vulnerable,” Zavabeti said.

“Our new nano-filter, made of stacked, atomically-thin sheets of aluminium hydroxide, is sustainable, environmentally-friendly, scalable and low cost.

“We’ve shown it works to remove lead and oil from water but we also know it has potential to target other common contaminants.

“Previous research has already shown the materials we used are effective in absorbing contaminants like mercury, sulfates and phosphates.

“With further development and commercial support, this new nano-filter could be a cheap and ultra-fast solution to the problem of dirty water.”

The liquid metal chemistry process developed by the researchers has potential applications across a range of industries including electronics, membranes, optics and catalysis.

“The technique is potentially of significant industrial value, since it can be readily upscaled, the liquid metal can be reused, and the process requires only short reaction times and low temperatures,” Zavabeti said.

Project leader Professor Kourosh Kalantar-zadeh, Honorary Professor at RMIT, Australian Research Council Laureate Fellow and Professor of Chemical Engineering at UNSW, said the liquid metal chemistry used in the process enabled differently shaped nano-structures to be grown, either as atomically thin sheets or nano-fibrous structures.

“Growing these materials conventionally is power intensive, requires high temperatures, extensive processing times and uses toxic metals. Liquid metal chemistry avoids all these issues so it’s an outstanding alternative.”

How it works

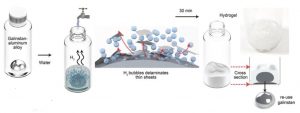

Water is added to a drop of a liquid metal (galinstan-Al). The skin is delaminated by hydrogen bubbles to form 2D sheets in the water, forming a hydrogel.

The groundbreaking technology is sustainable, environmentally-friendly, scalable and low-cost.

The researchers created an alloy by combining gallium-based liquid metals with aluminium.

When this alloy is exposed to water, nano-thin sheets of aluminium oxide compounds grow naturally on the surface.

These atomically thin layers – 100,000 times thinner than a human hair – restack in a wrinkled fashion, making them highly porous.

This enables water to pass through rapidly while the aluminium oxide compounds absorbs the contaminants.

Experiments showed the nano-filter was efficient at removing lead from water that had been contaminated at over 13 times safe drinking levels, and was highly effective in separating oil from water.

The process generates no waste and requires just aluminium and water, with the liquid metals reused for each new batch of nano-structures.

The method can be used to grow nano-structured materials either as ultra-thin sheets or nano-fibres.

These different shapes have different characteristics – ultra-thin sheets have high mechanical stiffness, while nano-fibres are highly translucent – which offers opportunities to tailor the shapes to enhance these properties for applications in electronics, membranes, optics and catalysis.

The findings are published in the journal Advanced Functional Materials (DOI: 10.1002/adfm.201804057).

Novel materials and FLEET

Deposition of atomically-thin materials is key to FLEET’s quest to develop a new generation of ultra-low energy electronics. Study co-authors Ali Zavabeti, Torben Daeneke, Isabela deCastro, Jian Zhen Ou, Benjamin Carey, and Kourosh Kalantar-Zadeh work within FLEET’s Enabling Technology A, developing novel two-dimensional semiconducting materials through theory, synthesis, and characterisation.

Deposition of atomically-thin materials is key to FLEET’s quest to develop a new generation of ultra-low energy electronics. Study co-authors Ali Zavabeti, Torben Daeneke, Isabela deCastro, Jian Zhen Ou, Benjamin Carey, and Kourosh Kalantar-Zadeh work within FLEET’s Enabling Technology A, developing novel two-dimensional semiconducting materials through theory, synthesis, and characterisation.

FLEET is an Australian Research Council-funded research centre bringing together over a hundred Australian and international experts to develop a new generation of ultra-low energy electronics.

Last year, FLEET researchers at RMIT developed a ground-breaking new method of depositing atomically-thin (two-dimensional) crystals using molten metals, described as a ‘once-in-a-decade’ advance.

More information

-

Novel materials team at RMIT. From left, Ali Zavabeti, Adam Chrimes, Ben Carey, Isabela Alves de Castro, Kouresh Kalantar-zadeh, Azmira Jannat, Nitu Syed, Torben Daeneke, Rebecca Orrell-Trigg

Kourosh Kalantar-Zadeh kourosh.kalantar@rmit.edu.au

- Follow FLEET at @FLEETCentre

- Website FLEET.org.au

- Youtube: future solutions to computation energy use

- Subscribe to FLEET news FLEET.org.au/news